This History of Public Library Service in Durham, 1897-1997 by Jessica Harland-Jacobs

On the Move and at a Standstill

The period between Griggs' resignation and the end of the Second World War witnessed growth in several areas for both of Durham's public libraries.

First, following the recommendations of the North Carolina Library Association, both the white and the black libraries sought to extend services to all citizens of the county.[51] The bookmobile was the means of accomplishing this goal for both libraries. Second, while the white library renovated its facilities to accommodate a Children's Room, the Durham Colored Library constructed an entirely new library. Finally both institutions played important roles in Durham's wartime service. But it was also a time of intense financial struggle and rebuilding. The Depression resulted in severe cutbacks and both libraries struggled to find the resources to fund their many programs and services. The frustrating combination of progress and stagnation that developed in this period would characterize the library's history for the next six decades.

When Griggs went to Raleigh, Clara Crawford took over as librarian. Crawford had served as cataloger and assistant librarian under Griggs for two years. Born in Alamance County and having attended Durham High School, she had received her education at Converse College in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and then the Carnegie Library School in Atlanta.[52] After working in Fredericksburg, Virginia, and Burlington, North Carolina, she went to work for Griggs, who had known Crawford when she had been a volunteer at the original library. Like her predecessor, Crawford was a devoted librarian and progressive, who firmly believed the library should play a central role in the uplift and education of the public.

Crawford, whom the Durham paper once described as no larger than the proverbial bar of soap after a week's wash,

was diminutive in stature but gigantic in dedication to the library.[53] She shared Griggs' commitment to providing library services to the rural population and sought to improve county extension by hiring a county librarian and sending the truck to every farm with interested white readers.

[54] After convincing the city and county to increase appropriations in 1926 Crawford quickly embarked on a program of house-to-house service, initiated on September 13 of that year. Working five mornings a week, the county librarian and the driver covered the county through eighteen different routes. When she launched this service, Crawford proclaimed: No excuse for ignorance remains. Opportunity for knowledge is not only knocking at the doors; it is honking at the front gate.

In its first five trips, Miss Kiwanis honked at the front gates of 116 homes and lent 131 books.[55]

Stanford L. Warren Library, circa 1917.

Miss Kiwanis carried fiction, non-fiction, and children's books. The county librarian provided guidance for those seeking advice about what

to read, but many already knew what they wanted--the most requested author was Zane Grey. Generally its targeted clientele greeted the bookmobile

with enthusiasm, but some were indifferent or even antagonistic, especially those who feared for their soul's welfare if a novel--anathema of Satan--be allowed to enter their homes.

[56] Aptly summarizing the service's contribution by remarking that September 13th marked the transformation of the Library from a relative[ly] static institution to a dynamic force for the diffusion of knowledge,

Crawford reported in January 1927 that county service had increased by 32.5 percent the previous year.[57]

Meanwhile, under strong leadership of Dr. Stanford L. Warren, the Durham Colored Library was undergoing a period of expansion as well. Warren, a physician and businessman who figured in every forward movement of the Durham community and was closely connected with the educational, economic, and business life,

had taken over as president of the Board of Trustees in 1923.[58] Through the efforts of Warren, the Board, and Hattie Wooten, the Durham Colored Library soon became a central community institution. In the mid-twenties, Wooten was spreading the word about the library and developing a number of programs. She advertised the library's services to the African American community by making sure that the library became an institution of interest

for visitors to Durham; she also opened the library to community groups and reported its programs to the Negro Yearbook.[59] In 1925, she gathered girls from the churches and established a Girls Club. The next year, with the cooperation of teachers in city schools, she initiated story hours. These programs as well as extended hours made the library available to the community, and the library soon became one of the African American population's primary gathering places.

The white library also sought to provide a meeting place for members of the community, particularly children. Like her predecessor, Crawford was a firm believer in children's services, and once she had set up house-to-house service, she launched a campaign to secure a children's librarian and a children's room. An inadequate supply of children's books and a lack of guidance for juvenile readers had resulted in a dramatic decrease in children's borrowing. In 1929 Crawford reported to the Board that she had 1784 children's books to supply 10,190 school children.[60] Moreover, existing facilities were inappropriate. Crawford saw the separation of the children and adult areas as essential; the intermingling of adults and children in the same room is a detriment to both,

she commented. Moreover, she viewed the public library as a refuge for children who were under-privileged or lacked parental guidance in the selection of appropriate reading material.[61] A room and a librarian dedicated solely to children could help the library fulfill these roles. Although Tilton had designed the basement to have a children's room with its own entrance, the library had not been able to finance the project to this point.

To remedy the situation, Crawford spearheaded a local drive to garner community support for better children's services. Once again, the library found its advocates among Durham's civic organizations. Annie Brooks, who had offered story hours to children while Griggs was in charge, became Chairman of the Children's Library Movement. Working tirelessly to create a public sentiment that would demand a separate room for the children,

the movement gained the endorsement of the Woman's Club, the American Business Club, and the Kiwanis Club. The strategy worked: the Kiwanis Club donated the funds to set up the children's room, which opened in 1930, and the Board agreed to hire a children's librarian.

Durham Public Library, Children's Room, circa 1926

In addition to providing house-to-house delivery and expanded children's services, the Durham County Library extended its reach in other ways during the late 1920S. Since 1923 it had been providing books to the Young Men's and Young Women's Christian Association camps. By 1927 it offered this service to Watts Hospital, the King's Daughter's Home, and the Woman's Club Fresh Air Camp. But all of these programs came to a grinding halt in the summer Of 1930 as Durham increasingly felt the effects of the Depression.

The library had been in a deplorable financial condition

since the previous summer. One reason for this, Crawford had surmised, was the library's position in the budget, under the amorphous heading Donations and Charities.

Crawford wrote to other librarians for information on their library's budgetary status and determined, not surprisingly, that where the library was recognized as its own department, it had more adequate support. Crawford would use this tactic-identifying a problem, writing to other libraries, gathering statistics, and educating the board, city councilors, and county commissioners-time and time again throughout her career. It generally worked. But this time the wider economic situation of the country made the improvement of the library's financial status impossible.

In mid-1929 unpaid bills and loans started to accrue, and by July 1930, the library was running a $7000 budget deficit.[62] The end of that year saw the drastic cutting of county extension; only truck service to county schools was maintained. After the library withdrew book deposits from camps and institutions and shortened its hours in late 1930, the Board dismissed the county librarian, truck driver, and children's librarian in 1931. The remaining staff--Crawford and one of her assistants--worked overtime to keep the library running. But even this was not enough; in a final drastic measure the city and county slashed appropriations to $3000, half of the amount provided in 1929.

In an attempt to stem further cuts and keep the library afloat, Crawford argued to city and county officials in 1931 that the library played a crucial role in a community suffering from economic depression. First, she made the point that although the library should maintain its collection of factual volumes,

it had to keep up its stocks of fiction since many people had so much extra time on their hands. Recreational reading, she claimed, plays a vital part in maintaining the morale of the community,

and she requested money to purchase more fiction. Crawford also felt the public library had an important service to perform in offering unemployed people the tools to prepare themselves for the future.[63]

The twenties had seen a dramatic expansion of services which were systematically rolled back during the Depression. As Crawford later remarked: A decade of carefully developed services were obliterated.

[64] The cuts caused her to re-evaluate the library's role and although she remained committed to providing all types of services, in the years after the Depression she emphasized its commitment to the recreational reader. Gradually, after 1934, Crawford was able to restore services and staff.

Although the budget could now handle normal operations, it could not address the library's primary need at this point: the deteriorating building. The structure built in 1921 was showing signs of disrepair and inadequacy. An article in 1935 reported that patrons of the library narrowly escaped injury from falling plaster recently.

[65] Moreover, another report stated, on rainy days librarians worked in teams to prevent water damage to books--one librarian would transfer books while another held an umbrella over her head. And after especially heavy downpours, one had to wear overshoes in the children's room.[66] Necessary improvements included building a balcony, putting on a new roof, installing a new furnace, repairing plumbing and plaster, repainting the entire building, and replacing the floor covering.

Crawford and the trustees decided to apply for a grant from the Works Progress Administration for $22,500 to assist with the repairs and constructing an addition.[67] Though they had received authorization from city and county officials to apply for the grant, the local authorities never managed to appropriate their share of local funds (55 percent) to secure the loan. As would be the case in the future, their refusal to fund library repairs and expansion resulted from the desire for a low tax rate and wide pressure for funds on the part of other institutions supported by local government.

[68] And in a move reflecting already established trend in the library's history, Crawford turned to local civic clubs to provide much-needed support.

In the spring of 1936, Crawford summoned all of the city's literary clubs to a meeting where they established the Library Committee of the Literary Clubs. Participating clubs included the Folio, Reviewers, Tourists, Up-to-Date, Canterbury, Halcyon, Book-of-the-Month, and the Pierian. Crawford envisioned a library advocacy group, and the literary clubs pledged to take on this role. As a result the committee sent delegations to meetings of city and county officials to stress the immediate necessity of repairing the Library building.

The group also publicized the need for an enlarged building and established an endowment for the purchase of books.[69]

Local officials agreed to perform the most necessary repairs in the fall Of 1936. In addition, a balcony was constructed to house the reference collection. However, the floor was not replaced, the building did not get painted, and the extension remained Crawford's dream. Consequently the library had to begin storing books in the basement of City Hall, the first in a series of stop-gap measures that would effectively chain the library to its 1921 facility for the next four and a half decades.[70]

As the twenties had been for the white library, the thirties and early forties were a period of transition and growth for the Durham Colored Library. The Depression seems to have hit the white library harder than the black library in part because the latter was already used to having a meager budget. In 1929, the white library had an operating budget of $15,321.00, while the black library received $1,690.00 from the city and county.[71] Although Crawford seems to have respected the accomplishments of her counterparts in Hayti and occasionally donated books she no longer wanted, there was little interaction between the black and white libraries in this period. Relations were cordial, but not collaborative. The Durham Colored Library Board considered Crawford a friend; apparently she would allow African Americans to go to the white library to request books they could not procure at their own library.[72] But her support only extended so far. Any improvements to the Durham Colored Library in this era came from within the African American community and were fostered by a new librarian. Their efforts ultimately culminated in the construction of a new building with money raised and borrowed from African Americans.

Upon the death of Wooten in November 1932, Selena Warren Wheeler became director of the Durham Colored Library. Born in Durham, she was the daughter of Stanford and Julia Warren; she married John H. Wheeler, trustee and secretary of the Board from 1931 to 1966 and lifetime advocate of the library. Through the efforts of Stanford Warren, Selena Warren Wheeler, and John Wheeler, Durham's African American library expanded its programs, built a new library, extended its county outreach, and secured significant increases in appropriations from local authorities.

Selena Warren Wheeler attended Howard University and originally intended to become a lawyer, but in late 1932 was asked to take over library operations from Wooten, who had fallen ill. A few months of temporary employment at the Durham Colored Library convinced Wheeler to pursue librarianship as a career, and she requested a leave of absence to attend Virginia's Hampton Institute, where she received her BS in Library Science in 1934. Upon her return to Durham, Wheeler's first priority was to extend the library's services to the rural population. She and Luvenia C. Hicks, who had filled in for Wheeler and then become her assistant, started county extension by using their cars to transport books in 1934. The following year they secured the assistance of the County Farm Demonstration Agent, T. A. Hamme, who took books with him on his trips to 4-H Clubs. Starting in 1936, he also delivered books to county schools.

By this point the Durham Colored Library had outgrown its facility. In 1938 the Board set up a Ways and Means Building Committee, which started to address the problem of overcrowding. One solution was to convert the second floor Browsing Room into a Reading Room and restrict afternoon hours to high school students. But these efforts did not solve the problem. In 1939 the Board resolved to build a new library by borrowing $24,000 from North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and $2,300 from Mechanics and Farmers Bank. Stanford Warren, who had led the movement to construct a new building, donated $4,000 to purchase a lot at the corner of Fayetteville and Umstead Streets, and John Sprunt Hill, founder of Central Carolina Bank and a philanthropist, contributed an additional $500.[73]

The opening of the new library on January 17, 1940 precipitated a dramatic expansion of services. Indeed, the early forties were banner years as far as the Stanford L. Warren Public Library (so named in honor of its primary benefactor) was concerned. The new library contained a Children's Room, and Wheeler initiated a Saturday Morning Story Hour in 1940, which proved so effective and popular that the library sponsored a Story Telling Institute the next year. Not limiting its offerings to books, the library also presented films and organized art exhibits.

On Wheeler's advice, the library also designated its collection of books on and by African Americans as a non-circulating, special collection during this period. Although the precise beginnings of the library's Negro Collection (as it was called at the time) are unknown, it seems to have had its origins in the 798 books Moore had gathered to establish the library in White Rock Baptist Church. The library made special arrangements with local book sellers to purchase books by African American authors at a reduced price. In 1942, Wheeler convinced the Board to use the Hattie B. Wooten Browsing Room to house the collection and subsequently did much to expand and classify the collection.[74] Over time, with the addition of many rare and out-of-print books, the collection became one of the best of its kind in the state.

In addition to offering more programs at the central library, the Stanford L. Warren Public Library reached out further into the rural community by setting up deposit stations in four Durham schools in 1940.[75] But this did not address the needs of adults in rural areas, so in October 1941 the Board agreed to purchase a bookmobile once funds were available. With contributions from various sources, including the state, the library was able to introduce bookmobile service in 1942.[76]

The Stanford L. Warren Public Library bookmobile made its first trip on February 10, 1942. Its revolving shelves held 600 books. Driven by Wheeler, it traversed the countryside, covered 575 miles each month, and was well received by rural communities. One woman served the staff her country cooking and another, in order to make a good impression, cleaned her house the day the bookmobile was expected. Very often the librarians had to assure potential patrons that there was no charge to borrow books, the most popular of which were fiction and religious. Bookmobile service quickly increased staff needs, so in March the Board hired two assistants and a custodian, who also served as bookmobile driver.

Riding around Durham County in a bookmobile in 1942, one would have noticed the war's increasing presence in the lives of North Carolinians. Twelve thousand men from Durham had registered for the draft and citizens participated in a wide variety of war-related activities, including war relief, victory gardening, and civilian defense. With the construction and opening of Camp Butner, part of which was within the county, Durhamites experienced both the prosperity and the troubles that accompanied serving the recreation needs of four thousand off duty servicemen each night.

Starting in 1942, both libraries had to make a number of adjustments. Staff were released for direct service, and WPA clerks assisted in keeping the libraries running. Energy conservation programs required reduced hours of opening. While the Civilian Defense Council used the white library to hold first aid classes, the United Service Organization (USO) took over the Browsing Room of Stanford L. Warren. Both libraries participated extensively in the Victory Book Campaign. By 1943, Crawford and her staff were so swamped with filling reference requests (usually about the articles of war and the Atlantic Charter) and providing library services to soldiers and other transients

that she asked for salary increases.

As it had during the First World War, the library served as an information bureau where people could come to find out about wartime activities and

regulations. Specifically, Crawford made the library a center of information on the War Price and Rationing Program. The Office of Price Administration wrote to Crawford in 1942 that they appreciated the work of the fine librarians in North Carolina. Even the book mobiles [sic] are carrying the Government program to every corner in North Carolina.

[77] The bookmobiles were doing more than carrying information; they transported books to farmers as well as servicemen's wives at Camp Butner. The operators of Durham Public Library's bookmobile felt they were contributing to the war effort by helping to lift the morale of the people through books.

The most popular morale-boosting authors of the period were Grace Livingston Hill, Temple Bailey, Zane Grey, Max Brand, and B. M. Bowell.[78]

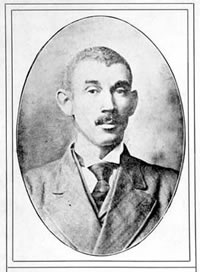

Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore, engraving, circa 1900.

Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore, engraving, circa 1900.The traumatic experiences of the Second World War, like those of the Depression, caused Crawford to contemplate the role of the library in society.

Having witnessed the chaos of the late thirties and war years, Crawford was extremely concerned about the vulnerability of the adult masses

and saw the library as playing a crucial role in their education. She was convinced of the enormous ideological power of books. In the war, just ended, a war inspired to destroy cultures,

she assessed, books were not only the evidence but the very instruments of competing cultures, and as such became weapons to wage war.

As storehouses of books, public libraries should serve as people's universities,

which were crucial to the preservation of democracy and freedom. Equally troubled by the dangers of atomic energy as she was by the chaos produced by Fascism and the war, Crawford believed that wide-spread education could add much to the public conscience which alone can save our civilization from unscrupulous use of this terrible, newly-released atomic force.

In short, she envisioned the library as a central institution for adult education.[79]

Miss Kiwanis

Crawford and the Board took the opportunity afforded by this new era to establish objectives for the library. Crawford aimed to extend library services to every person in Durham city and county. And, perhaps for the first time, when Crawford said every person

she meant it. It is imperative that the needs of our Negro citizens be kept constantly in mind,

she remarked. In reference to the Stanford L. Warren Library, she commented that the branch now established is excellent, but additional book collection and staff are badly needed

and suggested establishing branches in East and West Durham and Bragtown.[80] Setting up branches for white communities would also help relieve the intensely crowded

building. Indeed, instituting a system of branches was a central theme of both libraries' history during the next decades.