The Jeanes Teachers

The First Jeanes Teachers: Doing the Next Needed Thing

In 1907 Anna Jeanes, a Quaker, pledged one million dollars to the betterment of basic education for blacks in rural American schools.1 The Jeanes Fund was unique in several respects: It was created by a woman, had a racially integrated board, became international, and existed until 1968. While Jeanes and other Northern philanthropists like Julius Rosenwald envisioned students receiving better vocational and manual-labor-related instruction, the Jeanes supervising teachers found ways to use the funds that benefited their communities and did not limit their student’s dreams.

The first Jeanes supervising teacher, Virginia Estelle Randolph of Henrico County, Virginia [Related Link], set the standard for those who followed. Before becoming a Jeanes teacher, she had worked tirelessly to improve conditions in her school and community and had been made supervisor of all the black schools in the district because of her exceptional performance. In 1908 the Henrico County school superintendent asked the Jeanes Fund to provide money for Mrs. Randolph’s salary.2 At the end of her first year as a Jeanes teacher, the Fund’s board was so impressed with Mrs. Randolph’s accomplishments that they printed a thousand copies of her year-end report and mailed it to county superintendents throughout the South.3 Soon the Jeanes Fund was receiving requests from other county superintendents who wanted their own Jeanes supervising teacher. By 1909-1910, 129 Jeanes teachers were operating in thirteen Southern states.4

The Jeanes supervising teachers often began with little more than a teacher and a school building, and sometimes not even those. They had a missionary mentality, crusading tirelessly to improve conditions for their communities. Besides functioning as superintendent for the black schools, Jeanes teachers worked to improve public health, living conditions, and teacher training, started self-improvement and canning clubs, and truly did whatever was most needed in the community. The Jeanes teachers’s informal motto was to do “the next needed thing.”5 That this work was done in the South during the Jim Crow era, a time when any action by the black community to better itself might be met with harsh suspicion—or violence—by the dominant white community, is nothing short of astonishing.

Public Education in Durham County before Rosenwald Schools and Jeanes Teachers (1900-1915)

The modern era of public education in North Carolina dates to the administration of Gov. Charles Aycock, 1901-1905. A Democrat, his laudable advocacy of public school improvement is tainted by the troubling motivation for it, namely, the solidification of white supremacy in the state.6 Just a few years before, in 1898, Democratic white supremacists had violently overthrown the biracial city government of Wilmington, North Carolina, with the support of Aycock, party leader and future senator Furnifold Simmons, and Raleigh News and Observer editor Josephus Daniels.7

This campaign of hate came to Durham in July 1900. Ninth Street witnessed a parade with a telling campaign float: Sixteen “lovely young ladies” rode on a white float pulled by white horses. Banners on the sides read, “Protect Us with Your Vote.” Following the float, the West Durham White Supremacy Club, 300 strong, marched in formation. The parade ended in a rally in Erwin Park where over a thousand people listened to Democratic politicians stir up racial fears and hatred. Democrats campaigned in support of an amendment to the North Carolina Constitution that would effectively disenfranchise black voters (finishing the process that had started in 1898) and promised to improve the dismal state of public schools, linking the campaign for white supremacy and the improvement of public schools from the start.8 In a cold, calculating way, the “progressive,” racially “moderate” education reformers of North Carolina viewed the reestablishment of white rule as a necessary step in their campaign for improving public schools.

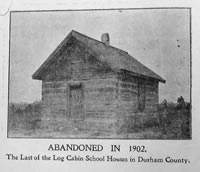

The improvement campaign was clearly focused on bettering schools for whites, with the goals of providing North Carolina with graded public schools,9 certified teachers, longer school terms, and a focus on practical, not classical, education. These goals required consolidating many small community schools into larger schools.10 The desire for parents to have their children in neighborhood schools is not new, and across the state many parents, black and white, resisted consolidation efforts. Durham was no exception. In 1903 C. W. Massey, superintendent of the Durham County School Board, wrote in his annual report:

This notion of multiplying school houses was preached in every community until at least every community had a school house, or rather in many instances, a school cabin….These schools were very convenient and very worthless….Before good schools could be built, these conditions had to be changed.11

Consolidation efforts did not extend to schools for blacks, and in fact, it was very common for schools no longer deemed fit for white students to be “recycled” into schools for black students. This was accomplished in two ways—by simply making the old white school a “new” black school or by tearing down the white school and rebuilding it in a different location as a “new” and usually smaller black school. The number of black schools stayed relatively constant from 1900 to 1930. [Related Link]

While the superintendent of schools and the school board made the decisions on consolidation, every school, including the African-American ones, had its own committee of three men responsible for the day-to-day operation of the schools, including hiring and firing teachers. Beginning in 1904, black schools were placed under the control of committeemen who also had responsibility for white schools.12 With the black committeemen gone, African-Americans possessed no formal authority over their schools or who would teach in them.

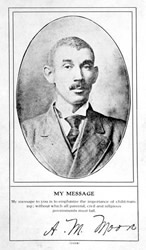

Despite this setback, black teachers and parents worked to improve their schools. In 1915 Dr. Aaron Moore, a physician, successful businessman, and community leader, wrote a tract called Negro Rural School Problem. Condition-Remedy 13 [Related Link] and began campaigning for an independent state inspector of Negro schools who could work to improve conditions. He also wrote to James Joyner, state superintendent of public instruction, about Julius Rosenwald’s interest in expanding his school building efforts into North Carolina, and to ask that Joyner actively pursue school funding from both the Rosenwald and Jeanes funds.14

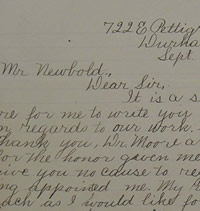

Dr. Moore had an ally at the state level. In 1913 Nathan C. Newbold, a white man who was paid by Jeanes and General Education Board funds,15 became the associate supervisor of rural education in the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction in Raleigh. He began to lobby county superintendents to hire their own Jeanes supervising teachers. Within two years North Carolina had thirty-six Jeanes supervising teachers, more than any other state.16

Frank Husband and the Start of Rosenwald Funds in Durham County (1915-1917)

Supported by Nathan C. Newbold and due to the continued lobbying of the black community led by Dr. Moore, the Durham County Board of Education finally asked for a Jeanes supervising teacher.17 Durham County’s first Jeanes supervisor, Frank Husband, was hired in June 191518 to address the dismal conditions of black schools in Durham County.19 Husband, an experienced local teacher, quickly set to work on school improvements, including building a Rosenwald school for the Rougemont community, where local clergyman Rev. William Smith had already been raising funds.20

During his short tenure as Jeanes supervisor, which lasted through the spring of 1917, Husband appears to have fought a battle against the county school board’s frustrating inactivity in this matter. The school would not be completed until 1919, four years after it was begun and after Husband had left the position of supervisor.21 Perhaps Mr. Husband had pushed too hard for the Rosenwald funds for the Rougemont School and had angered the superintendent or school board,22 because his contract was not renewed. In March 1917, Mattie Day replaced Husband as Jeanes supervising teacher for Durham County.23

Mattie Day, Homemakers Clubs, and World War I (1917-1923)

As Frank Husband and the black community of Durham County were beginning the fight to build better schools for their children, the United States was entering World War I. The question of whether the country had enough food to feed itself while sustaining the war effort was a real one, and gaining urgency. Before accepting the position of Jeanes supervising teacher in 1917, Mattie Day was running Durham County’s canning clubs, which provided local communities with information on how best to grow and can their own food.24 [Related Link] [Related Link] Nathan Newbold knew of her work and recommended her to replace Frank Husband.25 Miss Day continued to work with the canning clubs, and soon another critical activity was added to her duties.

During Day’s second year as supervisor—1918—Durham faced the Spanish flu pandemic, which was sweeping the world and would eventually kill at least fifty million people worldwide.26 Although the city and county schools were closed for six weeks, teachers who participated in efforts to contain the disease continued to be paid their salaries.27 Miss Day, as well as Mr. Husband (who had returned to being a classroom teacher) and many other teachers, worked with Mrs. Julia Latta, Durham County Health Department’s first black nurse, to fight the pandemic.28

Very little of Miss Day’s work is known, as none of the four required copies of her monthly and yearly reports survive. She did work to help the community get Rosenwald funding for new schools, and four were built during her tenure. The Rougemont School was finally finished29 and Walltown,30 Hickstown,31 and Lyon Park (Cemetery) schools32 were completed. In June 1923, the new school superintendent, John Carr, proposed that the county hire a supervisor of home economics for the black schools, and he recommended Miss Day for the position.33 Although the white schools had long had a supervisor for home economics, the Durham Morning Herald stressed that this was “a progressive step in negro (sic) education in Durham County. Each year Durham will be supplied with better trained cooks, servants, and housekeepers.”34 It is doubtful Miss Day viewed her goals in the same way the Herald did.35

Carrie Jordan (1923-1926) and Educational Achievement as a Source of Community Pride

The Board selected Mrs. Carrie T. Jordan as the new Jeanes supervisor for the coming school year.36 Mrs. Jordan was from a family with deep commitments to African-American education. Her father was Rev. Lawrence Thomas, pastor of Big Bethel AME Church (the oldest African-American church in Atlanta) and a founder of Morris Brown College.37 Mrs. Jordan graduated from Morris Brown and had been a teacher and principal in the Atlanta school system.38 She moved to Durham with her husband, Dr. Dock Jackson Jordan,39 who would teach for years at North Carolina Central University (then called the National Training School). Before accepting the Jeanes position, the fifty-three year old Jordan had taught at Hillside Park School.40

Mrs. Jordan was a highly skilled and progressive educator. In her 1923-24 annual report she followed the direction of the superintendent of schools, emphasizing spelling, geography, and nature study. In her report she relates how she “added life and interest to school.” [Related Link] [Related Link]

Mrs. Jordan wrote that, “We found many of the school houses in such poor condition that they were really unfit for use, and efforts were made to replace some of the worst ones with new buildings.”41 Much of her formidable energy was spent raising monies and organizing for new schools. She was responsible for the addition of twelve Rosenwald schools, including Hampton, Pearsontown, Union,42 Mill Grove,43 Lillian, 44 Rocky Knoll,45 and Sylvan.46 She worked on Bahama,47 Peaksville,48 Russell,49 Bragtown, and Woods,50 which would be completed over the summer of 1926. [Related Link]

Besides working for new schools, Mrs. Jordan began a new tradition for Durham County’s African-American schools—a county-wide commencement. The county commencements were a time that the black community could gather and celebrate. Dr. Valinda W. Littlefield wrote that the commencements “demonstrated the ability to overcome great odds with little financial and material support from the local and state educational establishments” and were a way to prove how much African-Americans valued education. She noted that academic achievement was proof to both the black and white communities of black potential and equality.51 Thousands of blacks gathering to celebrate the achievements of their children was an empowering event. Mrs. Jordan held contests for students in different areas of the county to find the students who would compete in contests at the county commencement at Durham State Normal School (now North Carolina Central University), exposing the best and the brightest of the county students to the world of higher education and encouraging them to believe that they could achieve great things. Despite this record of achievement, Mrs. Jordan declined to continue as the Jeanes supervising teacher at the end of the 1926 school year.52

Gertrude Tandy Taylor (1926-1930): The Final Rosenwald Schools and the Great Depression

In September 1926, twenty-six-year-old Mrs. Gertrude Tandy Taylor started work as the new Jeanes teacher for Durham County.53 She had been a teacher in the Mill Grove Colored School before her promotion.54 A graduate of Livingstone College, she would go on to earn a B.S. in education from Ohio State University and an M.A. from the University of Michigan.55 Her husband, Dr. James T. Taylor, taught at Durham State Normal School (now North Carolina Central University) from 1926 to 1960.56 Mrs. Taylor worked as the Durham Jeanes supervising teacher for almost twenty years under Superintendent Luther H.Barbour, returning to teaching when she left the position.57

During Mrs. Taylor’s first year, East Durham, Hickstown, Lyon’s Park, and Walltown schools became city schools, and the county lost 3,000 students.58 Most of Durham County’s African-American children were now in the city schools, with thirty-six percent or eight hundred black students remaining in the county schools.59 The students who switched to the city schools were automatically able to attend Hillside Park High School. County students had to apply to attend the school, which was the only black high school in the entire city and county. (Hillside has the distinction of being the first black high school in the state to receive a class “A” rating.60) [Related Link]

The county schools were notified when Mr. Julius Rosenwald visited Durham in 1928 on his way to Raleigh to celebrate the completion of the four-thousandth Rosenwald school.61 [Related Link] When Mr. Rosenwald toured some of the sixteen Rosenwald schools in Durham, Mrs. Taylor must have been one of the “local people anxious to entertain Mr. Rosenwald and show their appreciation.”62

Disasters helped Mrs. Taylor and the local communities build the last two Rosenwald schools in Durham County. In March of 1929 a fire destroyed the 1924 Rosenwald school at Pearsontown.6363 In August of that year, a windstorm destroyed the Page School..64 The county applied for and received Rosenwald funds and both buildings were completed in 1930. They were the last Rosenwald schools built in Durham County.

Working with a school board that was not very interested in black education,65 Mrs. Taylor, her predecessors, and the African-American communities built a total of eighteen Rosenwald schools. From 1921 to March of 1929, Durham County received $3,530 from the Jeanes Fund. In that time period Miss Day, Mrs. Jordan, and Mrs. Taylor raised a total of $5,964.88 (the equivalent of $75,119.47 in 2009 dollars). A paper from the Division of Negro Education reported:

These monies indicate the amount raised from private donations through the efforts of the Durham Jeanes Supervisors. Practically all of this money has been given by the Negro people and applied on construction of buildings, equipment and supplies.66

Durham’s Rosenwald building program was completed just before the beginning of the Great Depression. Mrs. Taylor continued to work to improve the schools of Durham and the lives of her students. In her December 1930 report, her only report for that year, she told of visiting all the schools and raising $121.33. Raising money during difficult times and encouraging generosity in a time of scarcity, Mrs. Taylor ended her report on a poignant note:

Many children brought clothes and food for the poor in their community. Old dolls and toys were repaired and given away. Most of the presents on the Christmas tree were made by the children. The supervisor was given a lovely vase made from a pickle jar, the inside lining of last year’s envelopes, red paint and shellac.67

Conclusions

The Jeanes supervisors and the African-American teachers of Durham County worked with what they had to make the lives of their students, parents, and communities the best they could be in the context of a legally entrenched inequality. Just as important, they taught a doctrine of self-improvement, hope in the future and racial pride. They acknowledged black achievement in yearly celebrations and small daily victories. As the Jeanes supervisors built schools and community organizations, they knew that their work was a political act in the Jim Crow South.

The Jeanes supervisors and their teachers believed in their ability to reach their students and they believed their students could achieve great things. Working under many hardships, black educators had to compensate for the lack of modern schools, textbooks, and equipment with vision and dedication. They all did “the next needed thing.” It has long been the conventional wisdom to think of the Jim Crow schools as a case study for second-class education. While the physical conditions of the schools and equipment were in all ways second class, the teachers were not. Led by the Jeanes supervising teachers, the teachers of Durham’s Rosenwald schools provided the foundation for the next generations who were to lead the long fight for civil rights. They are unsung heroes.

1 Jones, The Jeanes Teacher in the United States, 18 and Wright, Negro Rural School Fund, 3.

2 Jones, 42.

3 Ibid, 45.

4 Ibid, 47.

5 N. C. Newbold, Combined Jeanes Teacher Report for the School Year 1916-1917. Correspondence of the Director, Folder Negro Rural School Fund/Jeanes Foundation, Box 3, Division of Negro Education. Lists some of the work the Jeanes teachers performed: They "taught sanitation, industries and encouraged better schools by working for the extension of school terms. They helped to erect twenty-five new school buildings and found local monies to repair many others. They saw that one hundred and seventy-five schools were provided with sanitary outhouses and that five hundred children were provided with individual drinking cups. At five hundred and fifty-seven schools, the Jeanes teachers worked with the local community to improve the school grounds. Across the state, four hundred and eighty-three Improvement Leagues were organized for the parents of school children.” For the varied tasks the Jeanes teachers might do, one Jeanes teacher, identified only as Mayme, exemplified the Jeanes informal motto of doing “the next needed thing." She gave an account of some of her more unusual duties. She wrote that she had been asked how to improve soil, build a privy and rebuild steps. Others asked for her help in getting to the hospital and in burying a family member. A mother wanted her help to feed her children. She wrote letters and read them for those who asked. A man needed help to “to add my account at the commissary.” Finally, she said a person asked her to find a minister or Justice of the Peace to "get me married." See NASC Interim History Writing Committee, The Jeanes Story, 62.

6 Durham Daily Sun, 13 April 1900, “The Platform,” 2. Aycock’s platform stated: We denounce the administration of the Republican Party by which Negroes were placed in high and responsible official positions which ought to have been filled by white people….We heartily commend the Legislature for the passage of the election law of 1899 and we commend the General Assembly for appropriating $100,000 for the public schools and a pledge ourselves to increase the school fund so as to make at least a four-month school term in each year in every school district in the State.

7 The best account of the Wilmington coup d’etat is found in Democracy Betrayed edited by David Cecelski and Tim Tyson.

8 Durham Daily Sun, 21 July 1900, “West Durham a Winner!” 1.

9 Graded schools were schools where different grades were located in different rooms. A graded school facility could not be a one-room school.

10 Jones, 123.

11 Annual Report of the Schools of Durham County, 1902-03, 32.

12 Durham School Board Minutes, 7 June 1903. The school board in 1937--thirty-four years later--would decide to form “Negro Advisory Committees” for each black school. Their main duty was to “care for the school property and perform such other duties as may be defined by the County Board of Education.” The new committees could also recommend teachers to the county superintendent and the white school committee. See Durham School Board Minutes 7 July 1937.

13 A. M. Moore, 30 April 1915, Negro Rural School Problem. Condition-Remedy, General Correspondence of the Director File, Folder J-M, Box 48, Department of Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

14 A. M. Moore to J.Y. Joyner, 26 April 1915, General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder M, Box 48, Department of Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

15 Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow, 161. Like the Rosenwald Funwd, the GEB did not trust southern administrators to spend their money fairly and wanted a southern man who believed in their goals and would be loyal to them, while working within the Jim Crow administration. The General Education Fund was created by John D. Rockefeller and worked, among other things, TO improve the schools in the South. It often worked with the Jeanes and Rosenwald funds and focused on black education.

16 N. C. Newbold, Report for September 1916, Special Subject File, 1909-1926, Folder Reports of N. C. Newbold, Box 16, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives.

17 F. T. Husband to N. C. Newbold 16 September 1915, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder H, Box 2, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives.

18 Durham School Board Minutes, 15 June 1915.

19 Anderson, Durham County, 284. Charles H. Moore, the independent state inspector of negro schools made a report detailing the conditions of the Durham schools at this time. After visiting thirty-five counties, he found Durham County’s African-American schools were among the worst in the state. He wrote, “In no other county did I find the school houses upon the whole in such an inferior condition as I find them in this county for the colored school children.” Of the twenty-two schools, only one--East Durham--had more than one teacher. He reported that no new school house had been built during the last ten years, only two houses had ever been painted, and only one-third had desks, “while the rest had only shaky benches cast off from white schools.”

20 F. T. Husband to N. C. Newbold, 16 September 1915, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder H, Box 2, Division of Negro Education.

21 Rev. Smith would work four years with two Jeanes teachers before the Rougemont School would be built. see N. C. Newbold to H. Holton, 6 August 1919, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder H, Box 4, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives.

22 Mr. Husband wrote Mr. Newbold and asked him to visit the Rougemont community and see the interest in the school and work they had done on it. This may have angered Superintendent Massey. See F. T. Husband to N. C. Newbold, 12 September 1916, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder N, Box 3, Division of Negro Education. In Mr. Newbold’s reply to Mr. Husband, he indicated that Superintendent Massey did not feel it was the right time for the visit. See N. C. Newbold to F. T. Husband 13 September 1916, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder N, Box 3, Division of Negro Education.

23 Durham School Board Minutes, 6 August 1917.

24 W. H. Wannamaker to J. S. McKimmon, 28 June 1918, Folder 3, Box 1, WHWP. Dr. Wannamaker wrote the white state home demonstration agent A expressing his concern with the lack of canning in Durham County. “From what I can see in the county…we shall have to begin to urge the people to can this year. This sort of work needs constant stimulating.”

25 Durham School Board Minutes, 4 May 1917.

26 Durham School Board Minutes, 3 June 1919. Apparently some school boards decided to use the influenza epidemic as an excuse to close the black schools in their counties. In 1920 the state superintendent of schools Dr. E. C. Brooks wrote a circular letter to the county superintendents telling them that if they had not opened the black schools that they were violating the law. He also told them it was illegal to use any of the black teacher’s salaries for any other purpose. E. C. Brooks to County Superintendents 3 April 1920, General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder A-F, Box 71. Was Dr. Brooks not aware of this before the spring of 1920? Did some African-American schools stay closed over a year? Did he have any way or will to force the county superintendents to open these black schools?

27 Durham School Board Minutes, 7 October 1918.

28 Durham Morning Herald, “Partial List of ‘Flu Workers,” 22 November 1918, sec. 2, 1. See also Brown, Upbuilding Black Durham, 161.

29 N. C. Newbold to H. Holton, 6 August 1919, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder H, Box 4, Division of Negro Education.

30 W. F. Credle to S. L. Smith, 18 May 1923, General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1922-1923, Box 86, Department of Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

31 W. A. Credle to S. L. Smith, 18 May 1923, General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1922-1923, Box 86, Department of Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

32 W. F. Credle to Bessie Carney, 21 December 1922. General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder 1922-1923 Requisitions, Box 87, Department of Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

33 Durham School Board Minutes, 2 July 1923.

34 Durham Morning Herald, 3 July 1923, “Home Economics for Negro Girls,” 9. This idea that the function of black education was to provide whites with better servants had staying power and African-American educators tried to use it to their advantage. In 1931 this letter was sent to the white people of Roxboro by the Person County Training School faculty: “There go into your homes Negro girls and women whose economic conditions are such that these girls cannot take advantage of our splendid school opportunities that have been made possible by our good white friends of the town and county. The girls and young Negro women without adequate training are the ones we are hoping to reach through your cooperation. We are hoping to start an evening school for these girls, but we fear that they will feel reluctant to come. We are therefore, asking you to be kind enough to say a word of encouragement to them and to point out the necessity of their qualifying themselves to render a better grade of service than they are now rendering.” The letter ended with a survey asking questions like: “Does she know how to feed the baby? Does she know how to cook healthy food? How well does she clean the house?” See “Principal and Teachers of the Person County Training School to The White Families Employing Colored Servants,” 12 November 1931, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder D, Box 11, Division of Negro Education.

35 See Gender and Jim Crow by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, 160-161. “While paying lip service to the ideal of producing servants for white people, black women quietly turned the philosophy into a self-help endeavor and the public schools into institutions resembling social settlement houses. Cooking courses became not only vocational classes but nutrition courses where students could eat hot meals. Sewing classes …had the advantage of clothing poor pupils so that they could attend school more regularly.”

36 Durham School Board Minutes, 9 July 1923.

37 Jennifer Jordan, “The Thirtieth Anniversary of the Artishia and Fredrick Jordan Scholarship Fund,” Christian Recorder Online English Edition, 9 November 2006, 29 July 2009. Her father gave his library to the college when he died. His church, Big Bethel, was called “Sweet Auburn’s City Hall” because it had the largest public meeting space in that community.” In 1879, the Gate City Colored School, the first public school for African-Americans in the city, opened in the basement of Big Bethel. [ Related Link] For those growing up in Atlanta in the 1960s, the blue “Jesus Saves” on the steeply of big Bethel was a part of the skyline.

38 Dr. Jacqueline Jordan Irvin, e-mail message to author, 14 September 2009. Dr. Irvine, a great niece of Bishop Dock Jordan, is a Candler Professor Emeritus in Education from Emory University. She wrote that Mrs. Jordan was an elementary school principal in Atlanta and later taught at Morris Brown College. Mrs. Jordan also taught in the 1924 summer school at Durham Normal School. See Dr. J. E. Shepard to N. C. Newbold, 18 February 1924, Correspondence of the Director File, Folder S, Box 7, Division of Negro Education.

39 Jennifer Jordan, “The Thirtieth Anniversary of the Artishia, and Fredrick Jordan Scholarship Fund,” Christian Recorder Online English Edition, 9 November 2006, 29 July 2009. Dr. Dock. J. Jordan was the past president of Edward Waters and Kittrell, two AME colleges. Before coming to the National Training School, he taught at Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro. He taught history, social studies, psychology at the National Training School/The Durham State Normal School/ North Carolina College for Negroes until his retirement in 1939. He was also head of the department of education and often taught at the summer schools for local teachers. Dr Jordan and Mrs. Carrie Jordan had two children, daughter and a son. Her son was Bishop Frederick D. Jordan , the 72nd Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He was on the national board of CORE and was noted “as a fervent and militant advocate for civil rights.” Her daughter was Alice Julia Jordan, who worked for forty years in St. Louis for the division of children’s services and retired as the supervisor of that unit. She is buried near her mother and father in Beechwood Cemetery in Durham. [Related Link]

40 Durham City Directory 1923, 329.

41 Carrie T. Jordan, Annual Report of Rural Supervisor of Durham County Negro Schools, 1923-1924, 30 June 1924. Special Subject File, Folder Jeanes Fund, Miscellaneous, Box 2, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives.

42 Report of the North Carolina SOMETHING’S MISSING HERE 1923-1925, Budget of the Julius Rosenwald Fund, 21 July 1924, General Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder C, Box 91, Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

43 Durham Morning Herald, 15 April 1924, “Colored People Want A School: Bragtown Negroes Trying to Get Part of Rosenwald Foundation,” 3.

44 Ibid.

45 Durham School Board Minutes, 6 June 1925, 6 September 1925 and W. F. Credle to L. H. Barbour, 4 September 1925 Box 2, Correspondence of the Supervisor of the Rosenwald Fund File, Folder B, Division of Negro Education.

46 Durham School Board Minutes, 25 August 1925 and 6 September 1925. The patrons of the Sylvan Colored School came to the board with offers of money and materials for a new Rosenwald school and the board agreed to apply for the grant and build a school.

47 Durham School Board Minutes, 3 May 1926. Woods and Bahama patrons turned in $300 each for their Rosenwald school. See Durham Morning Herald, 6 April 1926.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid. The Russell School is the only surviving Rosenwald School. It sits near the junction of St Mary’s and Guess Road. It is now part of the Cain’s Chapel Baptist Church.

50 Ibid..

51 Littlefield, I Am Only One, 50. The white paper, The Durham Morning Herald, had five articles concerning these programs. This positive coverage of the African-American community was unprecedented. See Durham Morning Herald, 11 April 1924, “Groups Rallies at County Schools,” 4. Durham Morning Herald, 16 April 1924. “Commencement of County Negro Schools,” 9. Durham Morning Herald, 18 April 1924, “Negro Schools of Durham County To Hold Commencement of ON? Friday” 9. Durham Morning Herald, 19 April 1924, “Hundreds Are Preparing for Negro School Contest Here,” 25. Durham Morning Herald 20 April 1924 “Many Durham County Negroes in Attendance at School Exercises,” 8. The loss of the archive of the Carolina Times, Durham’s African-American newspaper, from its early years to the late 1930s is a great tragedy for researchers of Durham history. The articles of the county commencements in the Times would have been fascinating to read and to compare to those of the Herald. 52 Durham School Board Minutes, April 6 1926.

52 Durham School Board Minutes April 6 1926.

53 Durham School Board Minutes, 6 April 1926. Mrs. Taylor was born in Indiana and attended public school in Louisville, Kentucky. See “Funeral Program, Mrs. Gertrude Tandy Taylor, St. Titus’ P.E. Church, 27 January 1954.”

54 “Jeanes Teacher Aid Applications,” Series 4, Negro Rural School Fund, 1908-1937, File 10, “Missouri-North Carolina-Oklahoma,” Box 23, SEFR.

55 “Funeral Program, Mrs. Gertrude Tandy Taylor, St. Titus’ P.E. Church, 27 January 1954.” Mrs. Taylor did postgraduate work at the University of Saltillo in Mexico and the University of California at Berkeley. The Taylor Education Building was named for her husband, who taught at North Carolina Central University for 33 years. See History of NCCU School of Education, NCCU School of Education, 10 September 2000. Mr. André Vann, the NCCU archivist, provided this information for me.

56 Ibid. Dr. Taylor worked at NCCU from 1926 to 1960. He led the fight to equalize the salaries of black and white teachers and held several offices in the North Carolina Teachers Association, including that of president. He ran for the Durham City council in 1957 and was one of the founders of the Durham Committee on Negro Affairs--now the Durham Committee on the Affairs of Black People. After retiring from NCCU, he was appointed by Governor Terry Sanford to the Good Neighbor Council and served as its second chairman. See The Baltimore Afro-American, 7 April 1907, “Service for Dr. Taylor, Live-long NCCU Worker,” page 21. Dr. Taylor was a supporter of the NAACP, see Brown, Upbuilding Black Durham, 319.

57 Ibid. She would teach at Little River School from 1950 until her death on January 24, 1954. She had no children and was survived by her husband.

58 Durham School Board Minutes, 6 April 1926 and Durham School Board Minutes, 23 August 1927.

59 Durham Morning Herald, 14 Sept 1926, “County Schools Have A Good Opening With a Big Increase Shown in a Number of Them,” 5.

60 Durham Morning Herald, 30 May 1923, “Hillside School Gets Recognition,” 11. The paper described the new school as “one of the most modern and well equipped in the city system.” It replaced Whitted, which burned down in 1921. It was named for John Sprunt Hill, who donated the land on which the new school sat. It had been open only one year when it achieved its “A” classification. This school was located on Umstead Street. In the 1950s Hillside exchanged buildings with the Whitted Elementary School on Concord Street and was expanded.

61 Leloudis, Schooling the New South, 224.This training school/high school was located in Method and had eleven teachers. It was made of brick and had two shops classes, a library, and auditorium.

62 Durham Morning Herald, 1 April 1928, “Julius Rosenwald May Visit Durham,” Part IV, 8.

63 From F. W. Credle to S. L. Smith, 13 March 1929. Correspondence of the Supervisor of the Rosenwald Fund File, Folder S. L. Smith, Field Agent, Box 5, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives. It was rebuilt bigger with an extra classroom and a larger domestic science room. Patrons from this school wanted it rebuilt like most of the new city schools in fireproof brick. The county refused, saying it was too expensive. See Durham School Board Minutes, 2 April 1929. An example of the type of buildings the city was building in the African-American community was the new Lyon’s Park school. Built on the site of the 1923 Rosenwald School, the new Lyon’s Park city school was a large brick building and had an auditorium. The old West End School was consolidated into this school. See Durham Morning Herald, 31 May 1929. This school still stands and is used as a community center.

64 Durham Morning Herald, 5 August 1929. The board’s initial reaction was to try to repair the building at the “cheapest possible cost.” In September patrons from the school asked for something to be done, wanting a school for their children that year. They brought the board $175 toward their part of a Rosenwald school. See Durham School Board Minutes, 2 September 1929. The board decided they could build a Rosenwald school at Page if they could use the lumber from the destroyed school. See Durham School Board Minutes, 7 November 1929.

65 Note: The Pearsontown School was rebuilt after the first Pearsontown School burned. There were a total of seventeen standing Rosenwald schools, although the Fund built eighteen.

66 Some Facts About the Work of the Jeanes Industrial Supervisors, 1929, Correspondence of the Superintendent File, Folder N, Box 110, Public Instruction, Office of the Superintendent, NC State Archives.

67 Jeanes Reports, December 1930, Special Subject File, Folder Reports, Box 2, Division of Negro Education, NC State Archives.